- Issues

- Finances

- Consumers

- Competition

- CAN Culture

- The Future

Cultural, Arts, and Natural science institutions (CANs) enrich society by making accumulated knowledge and experience available to the public and scholars. The category includes museums, libraries, societies, and associations dedicated to preserving and serving the past and present. They have collections and expertise of great potential value.

But their existence as we know it is threatened because:

- They are not financially self-sustaining,

- Consumer interests are changing faster than the CANs' programs and services,

- They face serious competition from other mediums and technology, and

- Their inward- and backward-facing culture blocks change.

Looking toward the future, there are many ways these challenges can be overcome, using approaches adopted by exemplars from leading institutions, business, and competitors.

Click on a line of the table to review of each measure of financial performance:

As a practical matter, an institution's finances determine its direction and its ability to survive. They are of interest to donors, public officials, institutional management, and the public.

The panels below compare the financial performance of a sample of Cultural, Arts, and Natural Science institutions (CANs). An understanding of these measures is an essential basis for its development strategy and, in particular for its planning of products and services. They answer managment's question of "How are we doing?".

A few observations apply generally to several of the financial measures.

- Most of the financial perfomance measures show large differences among the institutions. In particular, the income earned by directly from the public varies greatly.

- Much of their income is spent internally to keep the institution running, rather than the delivery of services to the public

- In general, large institutions with broad national and international constituencies are the best performers. Smaller, local institutions with narrow constituencies are marginal.

- CANs typically report their figures to the IRS a year or two after the end of their fiscal years. The figures below are mostly based on 2005 fiscal years. We are currently updating the measures.

- Commercial, governmental, and public donors are increasingly restrictive with their support, with greater self interest than public interest.

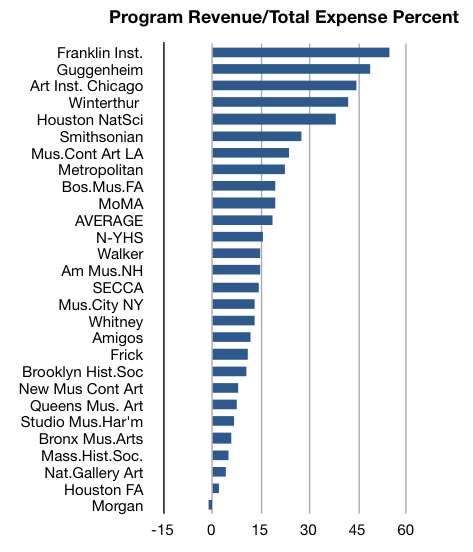

The revenue received from visitors, memberships and services, for CAN programs such as exhibits or use of assets, fails to cover associated expense. On average revenue offsets only 18% of costs. Their most visible output does not break even.

CAN programs are not self-sustaining because the economic model is flawed. Funds are spent to create an exhibit, for example, that only produces revenue once, even if the exhibit is distributed. Commercial enterprises spend once to develop a product that is sold many times.

This is important because the existance of CANS is justified by their benefit tothe public. The revenue is more than a financial figure -- it is a measure of the public's appreciatioinof the offered programs.

If programs do not attract a sufficiently broad segment of the public. The remaining funding must be supplied by three special interests: commercial, promoting their products and services, donors seeking recognition, and true believers that want to preserve artifiacts and knowledge for its own sake.

Most important aspect of the Revenue/Expense figures is that, on average, 82% of a CAN's funding depends on the interests and resources of other entitites with their own agenda's. The CANs generally then do not control their own desinies. They are not self supporting; they are vulnerable.

Program revenue as a percentage of total costs (about the same as total revenue) ranges from 50% to almost nothing, with an average of 18% for the selected institutions. The bulk of a CAN's expense do not produce public revenue.

Looked at the other way around, the average CAN obtains 82% of its income from donors, government, and other non-public sources, with two consequences:

First, it relies on the goodwill of a small number of large donors rather than its own efforts to attract revenue from a broad public audience

Second, it leaves the CAN subservient to the agendas of other organizations.

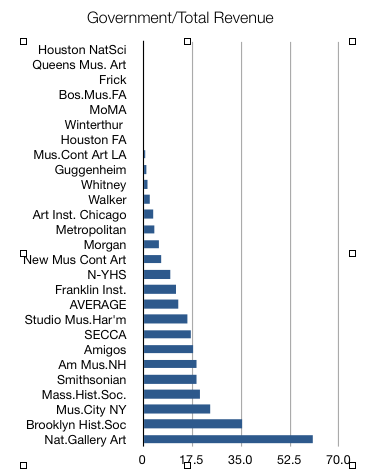

The institutions at the top rely least on funding from local, state, or federal government agencies. They tend to be independent, long-established, or well-endowed a long time ago. The average dependence of 12% compares to 18% from direct public contribution for programs and services.

Those relying more heavily on government are more likely to be government-sponsored. In the middle is the Smithsonian, created by a gift from Mr. Smithson but often thought of as a government institution, receives only 19% of its funding directly from governments.

While any funding is desirable in the short term, governments are an unreliable source because of conflicting demands, and leadership less attuned to old values.

To the extent that the general public does not want the CANs' programs enough to pay for them, their representatives will find it hard to justify paying with taxpayers' money. This leaves the government-created institutions at most risk.

There are, however, hidden subsidies from government and regulated utilities not included in the direct contributions. Long-term property leases and cut rate electricity or transportation are a benefit to some institutions thought to promote tourism or complement educational institutions. But these indirect contributions do not pay operating or program costs which must be funded from direct contributions.

There are, however, hidden subsidies from government and regulated utilities not included in the direct contributions. Long-term property leases and cut rate electricity or transportation are a benefit to some institutions thought to promote tourism or complement educational institutions. But these indirect contributions do not pay operating or program costs which must be funded from direct contributions.

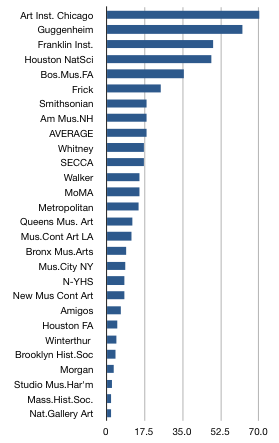

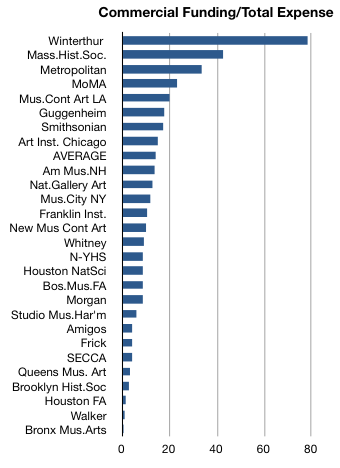

Commercial enterprises sponsor events and exhibits, often when the topic aligns with its own interests. There is a wide range of dependence, with an average of 13%.

Commercial enterprises sponsor events and exhibits, often when the topic aligns with its own interests. There is a wide range of dependence, with an average of 13%.

In general, the larger institutions with diverse collections are more successful in attracting these funds. The funds are less likely to be available to smaller institutions with narrower focus.

The rich get richer because the enterprises are looking for the largest possible exposure for their interests. The larger CANs face less risk of being dominated because they have larger and more diverse resources of their own. And of course, they have more resources to court large corporate donors, including trustee contacts.

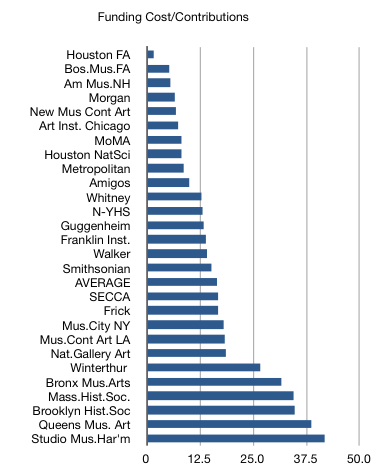

A similar pattern is seen for general fund raising costs as for commercial donations. CANs spend, on average, 16% of the funds raised in fund raising expense.

Many charitable organizations would be pleased to have 84% of funds raised be used for their mission. But this is analogous to a 16% interest rate, a high price to pay every year for income. Of course, it is a lot better than money spent on programs, which lose more than they cost.

Coming soon

Notes/inserts

Harvard obtains 35% of its overall operating budget from its endowment fund, with some schools obtaining over 50%. [Fabricant, NYT 4 Dec 08]

Coming soon

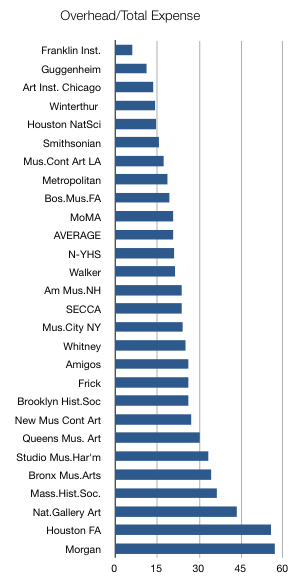

As with other measures, overhead varies considerably, with an average of 25% of expense. One-quarter of all revenue reseived goes to management, facilities, utilities, benefits, et al, excluding the manpower and other expense devoted to bringing programs to the public. Unlike other measures, the midrange is more consistant, ranging from 18% to 26%.

Here too, the figure is much higher than for commercial organization. It reflects the lack of an economic view by management, an internal orientation. The staff is more important than the pubic or the donors--the money is there so it can be spent.

Place cursor over graph to see numbers

At the end of the content/distribution chain, CAN material reaches the consumer, the ultimate source of funding. Consequently, the behavior of the consuming public must be understood and accommodated.

In developed economies, increased education and wealth enables consumers to make entertainment and education choices. Stated the other way around, content for mass audiences is less viable than it was when CANs were endowed, and their directions set. (A Doris Day movie will no longer make it.)

Technology in the form of cell phones, personal computers, and TV handsets facilitate consumer choices by providing two-way communication. The consumer can select what he wants to receive, and when. This means that the consumer more directly controls how the money flows from his pocket to the content originator.

Technology in the form of cell phones, personal computers, and TV handsets facilitate consumer choices by providing two-way communication. The consumer can select what he wants to receive, and when. This means that the consumer more directly controls how the money flows from his pocket to the content originator.

It is thus necessary for a CAN to determine very specifically what consumers are important to it. A fresh look may reveal entirely new audiences. Then it can proceed to develop products and distribution channels to attract the targeted audience. This externally-directed process will, of course, take into account the assets and expertise of the CAN. But it is contrary to the more usual course that begins with the CAN's collections and hopes for an audience.

It is thus necessary for a CAN to determine very specifically what consumers are important to it. A fresh look may reveal entirely new audiences. Then it can proceed to develop products and distribution channels to attract the targeted audience. This externally-directed process will, of course, take into account the assets and expertise of the CAN. But it is contrary to the more usual course that begins with the CAN's collections and hopes for an audience.

CAN management does not typically focus on competition, defined broadly to include all entities and activities that can take a piece of a consumer's entertainment (or education) time and attention. Understanding business models used by TV, music, film, information, publishing, and sports industries is a necessary first step in evaluating competition.

Content delivery is increasingly paid for by advertising, best exemplified by Google where over 90% of its revenue derives from ads. (Although this appears to be something new, it is just a transplantation of the old network broadcasting model where a network would deliver an audience to an avertiser.) Broadcasting, film production, and other single events, which require large financial commitments and large audiences at predetermined times, are being supplanted by on-demand, bite-sized deliveries via CDs and the internet.

The shift is enabled by analysis of credit card transactions on on-line site visits, making micro-segement marketing a possibility and a necessity, affecting both product design and choice of delivery channels.

A CAN's competitive position is complicated because some competitors may be donors and/or customers. Exhibits can be created with secondary distribution through TV, CDs, and film production.

Taken together, the scope of competitors and their marketing techniques must be considered by a CAN when developing and delivering products. The nature of competition is both a threat and opportunity. A separate project to recognize the most threatening is a good start. Since it is unlikely that CANs can compete broadly, they must identify a niche or expertise cluster and ruthlessly develop it.

As described under the Future tab, this concentration can be leveraged, preempting the competition.

"Survival of the fittest."

Herbert Spencer

"It is not the strongest species that survive, or the most intelligent, but the ones who are most responsive to change."

On the Origin of Species..., Darwin 1859.

Many CANs were created by donations of art, artifacts, and money with a particular orientation, but without long-term, sustaining resources. Such gifts carry the seeds of their own destruction.

In spite of mission statements vaguely professing to educate the general public (with the implication that it certainly needed it), the organization coalesced around the more easily defined tasks of protecting and preserving the collected items.

The typical CAN has two centers of attention. First, staff and expertise typically concentrate on the collection, the stuff in the attic. The underlying problem with this organization model is that the collections are not self-sustaining.

Second, wholesale fund raising is essential, employing two units: the board of trustees, and a dedicated 'development' team. These structures are poisonous over the long term. Trustees are enlisted for their money and contacts, rather than vision, ability to select effective management, and understanding of organizational economics. The development team's focus on fundraising; separate from program design, development, and delivery; fails to link the organization to the public, the ultimate sustaining force.

The two centers of attention are inward-looking; they serve to protect the institution rather than serving the public. The perspective is not unique to CANs. Two examples from business are similar, and demonstrate the consequences. For years General Motors build products that were good for the company, big vehicles and associated big profits. The long-standing view was that it was their role to determine what was good for their costomers. Consequently, when the road to sucess turned, GM plowed straight ahead into a gully. As a second example, consider 'investment banks' which designed products for their own profitability with compensation plans that fed the strategy. Their customers' welfare was ignored until it was too late to 'take it back'.

Inward-looking corporate analogies are more than skin deep:

| Corporate Characteristic | CAN Situation |

|---|---|

| The companies were highly leveraged, using other people's money. | CANs short-term survival depends on other peoples' money -- donations and grants. |

| Assets were considered a measure of strength. | Collections are the foundation of existance. |

Executives were rewarded according to organization-centric, short-term goals. |

Curators are rewarded based on academic and peer rank related to collections, not long-term goals. |

| Marketing units were primarily sales operations. | Curators and fund raisers are not focused or organization strategy. |

Differences are just as revealing:

| Corporate Behavior | Can Situation |

|---|---|

| Unproductive assets are sold. | Selling collected items are generally prohibited. Maintain 'Dead' assets. |

| Customer demographics, buying patterns, and interests well-known. | Customer data routinely ignored. |

| Organization and individual performance measured and compensated | Staff rewarded based on credentials, not performance. |

| All assets have a, stated quantitative value. | Asset values range from priceless to nothing. |

| Organized by business function | Organized by expertise. |

Recognize that changing an organization's culture is difficult, often impossible. See The Future tab for suggestions.

The typical CAN is not well positioned for the future. But each of the current limitations has been experienced and overcome by other organizations. Some examples are described at the end of this tab. But first, consider the path to get from here to there.

Many organizatioal forms can be successful so there are choices. Each CAN can decide what it wants to be when it grows up. But first, make sure that it has the knowledge base.

Preparing for Change

Expand the horizon of professional staff. Learn how:

- Businesses organize to deliver products and services,

- Competitive organizations hire and promote key personnel.

- Product managers and development groups identify opportunities and create new products,

- To set goals for executives and staff positions, and how they are compensated,

- Assets are converted into revenue

- And by whom critical decisions are made,

- Productivity of space is measured (particularly in retail),

- To estimate and compare financial returns, and norms.

- And so forth.

Appraise existing organization.

Identify and evaluate the inherent strengths of the organization as it is. Take stock of collections, people, and facilities. The immediate future will most likely be an incremental step forward from the present position.

Collections. Existing collections are the place to start because they have probably defined the organization to this point. But they are the past, not necessarily the future. Test items or groups of items with questions such as:

- What would be the effect if the item were to disappear today?

- Who would notice, who would care? Would theylike to have the item? Shouldn't they?

- How much does it cost to retain, maintain?

- What is its value? What is its best economic use? To whom?

- What story can it be used to tell.

The answers to such questions should be constrained to be objective, not a justification of the past. Prepare for subsequent action by placing items in categories such as: potential economic use over next ____ years, junk, too-expensive-to-maintain, orphans in need of foster care, etc. The process will be difficult because it brings to the surface past assumptions, challenges founding concepts, and threatens individuals' professional standings.

Each of those aspects of an institution has a constituency, value, and can be defended. But preserving such aspects in the abstract is not the issue. Without an economic underpinning, those aspects will not be preserved. The issue at hand is the best use of an institution's strengths going forward. See The value of Priceless Things, [^^^ link needed ^^^].

The answers of course will not be simple--use triage or 'multrage'.

If an item falls to the bottom but is entailed, return it.

Create a category that tests values such as priceless, invaluable, . Solicit funds for maintainence and storage of such items in perpetuity or give them to someone whow will provide such a guarantee. If it proves impossible, you have the answer. Your organization should not carry the burden items proven valueless. For more on the value of non-commercial items, see the article ...[link to article]

, beginning

Choose Institutional Framework

A vision of the future must precede the journey. Some orienting principles are needed, such as:

- Revenue received directly from the public must cover ____ % of costs.

- At least ____ % of collected items will be put to economic use in any ___ year period.

- The organization will be shaped so that responsibilities can be unambiguously assigned and evaluated.

- Success of the organization, units, and individual units will be quantitatively measured.

- Responsibilities, tasks, and assignments will be determined by agreement among managers, staffs, and experts.

Such a framework does not mean that the organization is to be run as a business, but it can provide a reference against which specific ideas and accomplishments can be tested.

Fill in Framework

Internally, identify skills, resources, and facilities that are unique strengths. An institution's collections and history may be a strength, but may be the primary challenge.

Future ^^^ Business model, page PU p 2